Dec. 4, 2012, 7:03 a.m. by tvinar

Topics: Probability

Modeling Random Genomes

We already know that the genome is not just a random strand of nucleotides; recall from “Finding a Motif in DNA” that motifs recur commonly across individuals and species. If a DNA motif occurs in many different organisms, then chances are good that it serves an important function.

At the same time, if you form a long enough DNA string, then you should theoretically be able to locate every possible short substring in the string. And genomes are very long; the human genome contains about 3.2 billion base pairs. As a result, when analyzing an unknown piece of DNA, we should try to ensure that a motif does not occur out of random chance.

To conclude whether motifs are random or not, we need to quantify the likelihood of finding a given motif randomly. If a motif occurs randomly with high probability, then how can we really compare two organisms to begin with? In other words, all very short DNA strings will appear randomly in a genome, and very few long strings will appear; what is the critical motif length at which we can throw out random chance and conclude that a motif appears in a genome for a reason?

In this problem, our first step toward understanding random occurrences of strings is to form a simple model for constructing genomes randomly. We will then apply this model to a somewhat simplified exercise: calculating the probability of a given motif occurring randomly at a fixed location in the genome.

An array is a structure containing an ordered collection of objects

(numbers, strings, other arrays, etc.).

We let

A random string is constructed so that the probability of choosing each subsequent symbol is based on a fixed underlying symbol frequency.

GC-content offers us natural symbol frequencies for constructing random DNA strings.

If the GC-content is

In practice, many probabilities wind up being very small.

In order to work with small probabilities, we may

plug them into a function that "blows them up" for the sake of comparison.

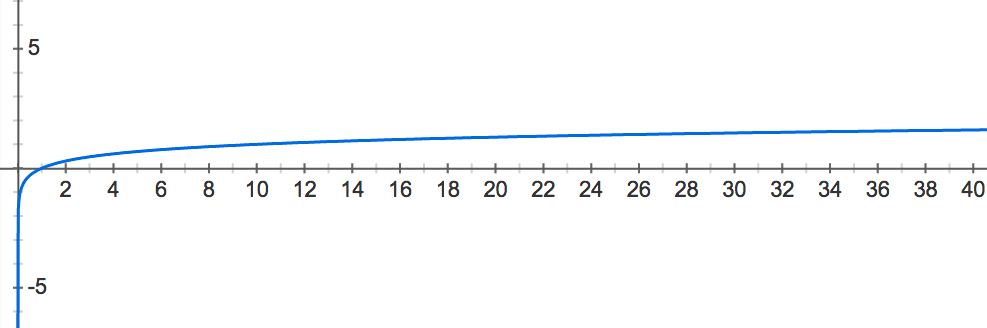

Specifically, the common logarithm of

See Figure 1

for a graph of the common logarithm function

Given: A DNA string

Return: An array

ACGATACAA 0.129 0.287 0.423 0.476 0.641 0.742 0.783

-5.737 -5.217 -5.263 -5.360 -5.958 -6.628 -7.009

Hint

One property of the logarithm function is that for any positive numbers

$x$ and$y$ ,$\log_{10}(x \cdot y) = \log_{10}(x) + \log_{10}(y)$ .