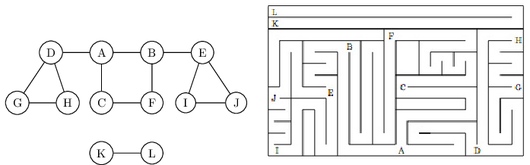

Depth-first search in undirected graphs

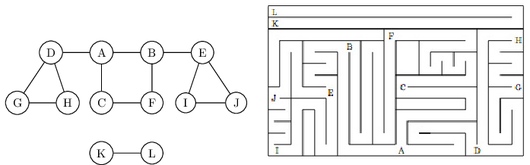

Exploring mazes

Depth-first search is a surprisingly versatile linear-time procedure that reveals a wealth of

information about a graph. The most basic question it addresses is,

What parts of the graph are reachable from a given vertex?

To understand this task, try putting yourself in the position of a computer that has just been

given a new graph, say in the form of an adjacency list. This representation offers just one

basic operation: finding the neighbors of a vertex. With only this primitive, the reachability

problem is rather like exploring a labyrinth.

You start walking from a fixed place

and whenever you arrive at any junction (vertex) there are a variety of passages (edges) you

can follow. A careless choice of passages might lead you around in circles or might cause you

to overlook some accessible part of the maze. Clearly, you need to record some intermediate

information during exploration.

This classic challenge has amused people for centuries. Everybody knows that all you

need to explore a labyrinth is a ball of string and a piece of chalk. The chalk prevents looping,

by marking the junctions you have already visited. The string always takes you back to the

starting place, enabling you to return to passages that you previously saw but did not yet

investigate.

How can we simulate these two primitives, chalk and string, on a computer? The chalk

marks are easy: for each vertex, maintain a Boolean variable indicating whether it has been

visited already. As for the ball of string, the correct cyberanalog is a stack. After all, the exact

role of the string is to offer two primitive operations—unwind to get to a new junction (the

stack equivalent is to push the new vertex) and rewind to return to the previous junction (pop

the stack).

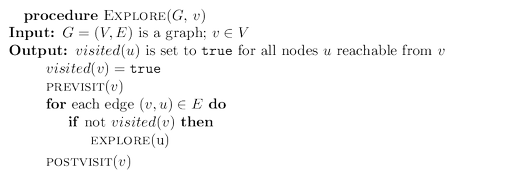

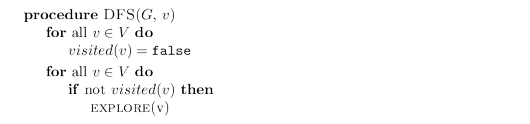

Instead of explicitly maintaining a stack, we will do so implicitly via recursion (which

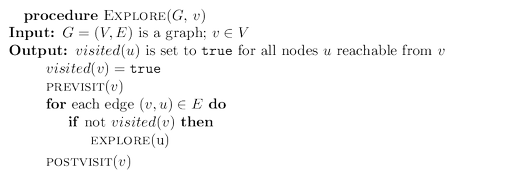

is implemented using a stack of activation records). The resulting algorithm is shown in

the following picture.

The $\tt{previsit}$ and $\tt{postvisit}$ procedures are optional, meant for performing

operations on a vertex when it is first discovered and also when it is being left for the last

time. We will soon see some creative uses for them.

More immediately, we need to confirm that $\tt{explore}$ always works correctly. It certainly

does not venture too far, because it only moves from nodes to their neighbors and can therefore

never jump to a region that is not reachable from $v$. But does it find all vertices reachable

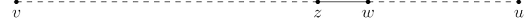

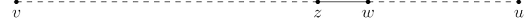

from $v$? Well, if there is some $u$ that it misses, choose any path from $v$ to $u$, and look at the

last vertex on that path that the procedure actually visited. Call this node $z$, and let $w$ be the

node immediately after it on the same path.

So $z$ was visited but $w$ was not. This is a contradiction: while the explore procedure was at

node $z$, it would have noticed $w$ and moved on to it.

Incidentally, this pattern of reasoning arises often in the study of graphs and is in essence

a streamlined induction. A more formal inductive proof would start by framing a hypothesis,

such as “for any $k \ge 0$, all nodes within $k$ hops from $v$ get visited.” The base case is as usual

trivial, since $v$ is certainly visited. And the general case—showing that if all nodes $k$ hops

away are visited, then so are all nodes $k + 1$ hops away—is precisely the same point we just

argued.

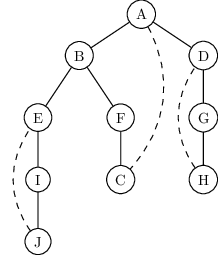

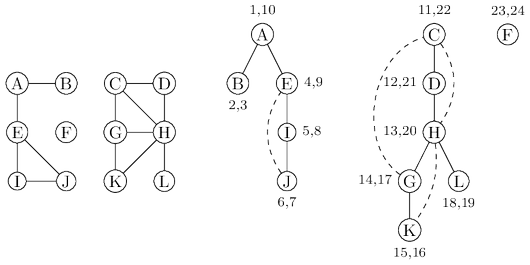

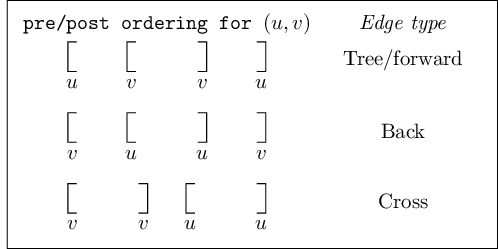

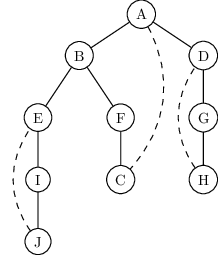

The following figure shows the result of running ${\tt explore}$ on our earlier example graph, starting

at node $A$, and breaking ties in alphabetical order whenever there is a choice of nodes to

visit. The solid edges are those that were actually traversed, each of which was elicited by

a call to explore and led to the discovery of a new vertex. For instance, while $B$ was being

visited, the edge $B$--$E$ was noticed and, since $E$ was as yet unknown, was traversed via a

call to ${\tt explore}(E)$. These solid edges form a tree (a connected graph with no cycles) and are

therefore called tree edges. The dotted edges were ignored because they led back to familiar

terrain, to vertices previously visited. They are called back edges.

Depth-first search

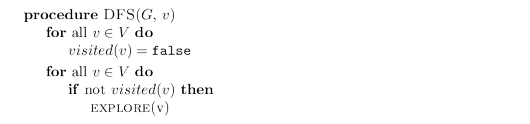

The ${\tt explore}$ procedure visits only the portion of the graph reachable from its starting point.

To examine the rest of the graph, we need to restart the procedure elsewhere, at some vertex

that has not yet been visited. The algorithm of shown below, called depth-first search (DFS),

does this repeatedly until the entire graph has been traversed.

The first step in analyzing the running time of DFS is to observe that each vertex is

${\tt explore}$’d just once, thanks to the ${\tt visited}$ array (the chalk marks). During the exploration

of a vertex, there are the following steps:

1. Some fixed amount of work—marking the spot as visited, and the ${\tt pre/postvisit}$.

2. A loop in which adjacent edges are scanned, to see if they lead somewhere new.

This loop takes a different amount of time for each vertex, so let’s consider all vertices to-

gether. The total work done in step 1 is then $O(|V|)$. In step 2, over the course of the entire

DFS, each edge $\{x, y\} \in E$ is examined exactly twice, once during ${\tt explore}(x)$ and once

during ${\tt explore}(y)$. The overall time for step 2 is therefore $O(|E|)$ and so the depth-first search

has a running time of $O(|V| + |E|)$, linear in the size of its input. This is as efficient as we

could possibly hope for, since it takes this long even just to read the adjacency list.

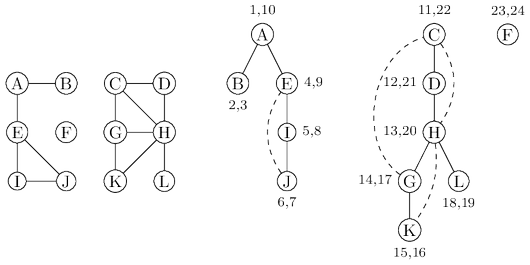

The following shows the outcome of depth-first search on a $12$-node graph, once again

breaking ties alphabetically (ignore the pairs of numbers for the time being). The outer loop of DFS

calls ${\tt explore}$ three times, on $A$, $C$, and finally $F$. As a result, there are three trees, each

rooted at one of these starting points. Together they constitute a forest.

Depth-first search can be easily used to check whether an undirected graph is connected

and, more generally, to split a graph into connected components.

Previsit and postvisit orderings

We have seen how depth-first search—a few unassuming lines of code—is able to uncover the

connectivity structure of an undirected graph in just linear time. But it is far more versatile

than this. In order to stretch it further, we will collect a little more information during the

exploration process: for each node, we will note down the times of two important events, the

moment of first discovery (corresponding to ${\tt previsit}$) and that of final departure (${\tt postvisit}$).

The figure above shows these numbers for our earlier example, in which there are $24$ events. The

fifth event is the discovery of $I$. The $21$st event consists of leaving $D$ behind for good.

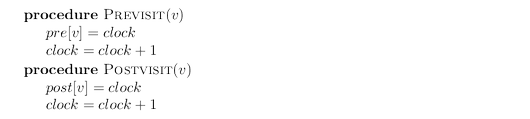

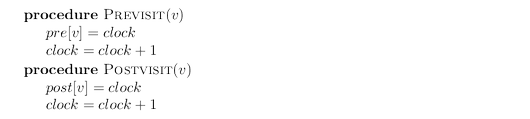

One way to generate arrays ${\tt pre}$ and ${\tt post}$ with these numbers is to define a simple counter

${\tt clock}$, initially set to $1$, which gets updated as follows.

These timings will soon take on larger significance. Meanwhile, you might have noticed from

the graph above that:

Property For any nodes $u$ and $v$, the two intervals $[pre(u), post (u)]$ and $[pre(v), post(v)]$ are

either disjoint or one is contained within the other.

Why? Because $[pre(u), post(u)]$ is essentially the time during which vertex $u$ was on the

stack. The last-in, first-out behavior of a stack explains the rest.

Depth-first search in directed graphs

Types of edges

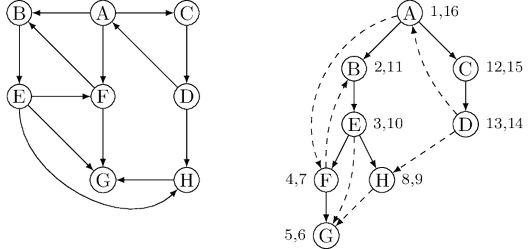

Our depth-first search algorithm can be run verbatim on directed graphs, taking care to

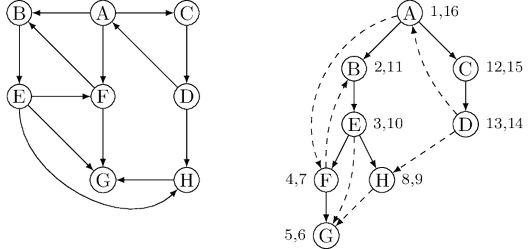

traverse edges only in their prescribed directions. The following figure shows an example and the search

tree that results when vertices are considered in lexicographic order.

In further analyzing the directed case, it helps to have terminology for important relationships

between nodes of a tree. $A$ is the root of the search tree; everything else is its descendant.

Similarly, $E$ has descendants $F$, $G$, and $H$, and conversely, is an ancestor of these three nodes.

The family analogy is carried further: $C$ is the parent of $D$, which is its child.

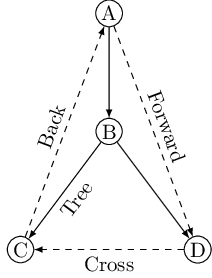

For undirected graphs we distinguished between tree edges and nontree edges. In the

directed case, there is a slightly more elaborate taxonomy:

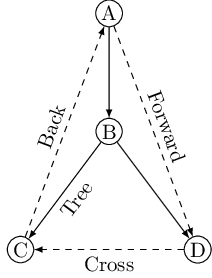

- Tree edges are actually part of the DFS forest.

- Forward edges lead from a node to a nonchild descendant in the DFS tree.

- Back edges lead to an ancestor in the DFS tree.

- Cross edges lead to neither descendant nor ancestor; they therefore lead to a node that has already been completely explored (that is, already postvisited).

The graph above has two forward edges, two back edges, and two cross edges. Can you spot them?

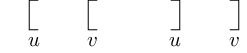

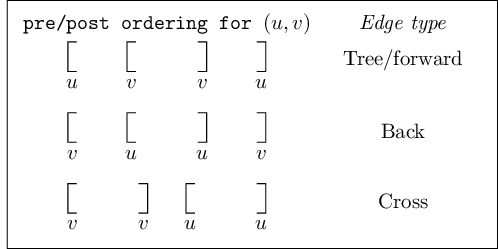

Ancestor and descendant relationships, as well as edge types, can be read off directly

from ${\tt pre}$ and ${\tt post}$ numbers. Because of the depth-first exploration strategy, vertex $u$ is an

ancestor of vertex $v$ exactly in those cases where $u$ is discovered first and $v$ is discovered

during ${\tt explore}(u)$. This is to say ${\tt pre}(u) < {\tt pre}(v) < {\tt post}(v) < {\tt post}(u)$, which we can

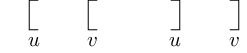

depict pictorially as two nested intervals:

The case of descendants is symmetric, since $u$ is a descendant of $v$ if and only if $v$ is an

ancestor of $u$. And since edge categories are based entirely on ancestor-descendant relationships,

it follows that they, too, can be read off from ${\tt pre}$ and ${\tt post}$ numbers. Here is a summary of

the various possibilities for an edge $(u, v)$:

You can confirm each of these characterizations by consulting the diagram of edge types. Do

you see why no other orderings are possible?

Using the just introduced edge types one can check whether a given graph is acyclic or not in linear time.

Depth-first search can also be used to find a linearization of a given dag as well

as splitting any directed graph into strongly connected components.

Source: Algorithms by Dasgupta, Papadimitriou, Vazirani. McGraw-Hill. 2006.

DFS visualisation by David Galles: http://www.cs.usfca.edu/~galles/visualization/DFS.html.